9 May 2016 marks yet another extraordinary meeting for the Eurogroup. The agenda includes discussing the status of the third financial assistance programme to Greece and the sustainability of Greece’s public debt. Ministers stand to face hard choices.

The IMF has been vocal about the need for debt reduction. Christine Lagarde, the Managing Director of the IMF, sent a letter on Thursday to euro-area finance ministers regarding the issue, which was subsequently leaked. She argues that fiscal consolidation measures agreed upon thus far will only reach a GDP primary surplus of 1.5% by 2018, instead of the original 3.5% target desired by the third financial assistance programme.

According to the IMF, reaching the 3.5% target would not only be difficult, but could even be counterproductive. If further adjustment relied on tax hikes levied against a narrow base and excessive discretionary spending cuts, it may skirt around the bigger issue of long-overdue public sector reforms in the pension and tax systems. The IMF also believes that even if the 3.5% primary balance target could be reached in 2018, future Greek governments would likely relax it. The IMF therefore proposes a target of 1.5% of GDP primary surplus from 2018 onward and public debt restructuring (aside from IMF loans).

The IMF deserves adequate praise for its courage to learn from past mistakes. In 2010, the IMF wholeheartedly endorsed the target of 6% of GDP primary surplus during the first financial assistance programme. The programme was based on overly-optimistic assumptions and the IMF resolutely opposed debt restructuring. In 2012, the IMF endorsed the target of 4.5% of GDP primary surplus during the second financial assistance programme. The result was the vicious fiscal adjustment/GDP contraction circle. This led to greater uncertainty about Greek membership in the euro, which further undermined economic and social developments. European contributors to the first two Greek financial assistance programmes are still obliged to admit these mistakes.

Although we share many arguments the IMF put forward in its new approach, we argue that the IMF goes too far in requesting such low levels of primary surplus. In 2013, an IMF research paper found that the average primary surplus for 26 major debt reductions in advanced economies over the last three decades was 3.1% of GDP. Primary surpluses larger than 1.5% were maintained in Europe’s other two high-debt countries: Belgium had an average of 4.3% between 1987-2008, while Italy saw 3.1% between 1992-2008. In the coming years, many European countries will need to reach higher than a 1.5% of GDP primary surplus target in order to calm concerns about debt sustainability.

Therefore, we see no fundamental problem with a 3.5% of GDP target, though it could be reduced slightly, as a 2.5% target appears reasonable in our simulations below. But the key problem is timing: Greece has suffered the largest fiscal adjustment and output decline of any country in the world for the last six years, but continues to be asked for further fiscal adjustment.

Of course, Greece was primarily responsible for the mess that necessitated its bail-out in 2010, and when a country has unmanageable debt and an excessive budget deficit, it must adjust. But design failures from the first two financial assistance programmes exacerbated Greece’s falling GDP. Thus the responsibility for the failure of the first two financial assistance programmes falls both upon Greece and official creditors, as is argued in this article.

Further fiscal adjustment should be delayed several years until economic growth resumes. What Greece needs most right now is hope for the future. This hope will not materialize until economic growth and job creation resume. Economic growth would also improve the primary balance, even without further fiscal adjustment, and thereby contribute to reaching the long-term primary balance target. In fact, many positive developments suggest that a new growth model is in the works in Greece. Let us first see growth resume, and then continue with fiscal adjustments.

Therefore, a key consideration we propose to the Eurogroup is a delayed fiscal adjustment path, potentially making it conditional on GDP growth.

And as for Greek public debt?

The greatest peculiarity we see is that at the end of 2015, 75% of Greek public debt was in the form of official loans. Bond holdings of European central banks amounted to an additional 6%, while some additional percentage was held by (largely state-owned) Greek banks. The share of official loans is bound to increase in the coming years. Given the dominant share of official creditors, the high level of debt and all the uncertainties that characterise the Greek economy, it is unreasonable to assume that Greece will be able to return to market borrowing at an affordable rate in the foreseeable future(*).

Even if Greece reaches an overall budget balance by 2018, new borrowing will be needed in the future. The current €16bn loan from the IMF needs to be repaid by 2021, and the €20bn bond holdings of the ECB and national central banks by 2026. The current stock of €3bn pre-2012 bonds, which were not restructured in 2012, also needs to be repaid. Repayment of the remaining €31bn bonds which resulted from the 2012 debt restructuring will start in 2023. The €53bn bilateral loans from euro-area partners granted in the first financial assistance programme will have to be repaid between 2020-2041, according to current schedule.

Thus, like it or not, euro-area partners either have to fund the new borrowings of Greece for decades at the preferential ESM lending rates, or implement a debt reduction plan drastic enough to make a return to market borrowing possible.

To put it differently, Greek public debt does not look sustainable if the country has to return to market borrowing at the end of the third bail-out programme, but could be sustainable if preferential ESM funding continues in the long-term.

There seems to be strong opposition for a large nominal haircut, so we presume funding will continue beyond the horizon of the current third bail-out programme.

Future funding needs can be reduced by extending maturities and grace periods of existing official loans, returning all profits that European central banks make on their earlier purchase of Greek government bonds back to Greece, eliminating the 50 basis points spread which is still added to the Euribor for the bilateral loans that euro-area partners provided in the first bail-out, and offering further deferrals of interest payments. Swapping official loans to GDP-indexed loans would also reduce uncertainty, since loan value would reduce automatically if GDP growth falls again, while also giving creditors more in return if GDP outperforms current projections. In fact, the menu of choices seems much the same since we assessed the options in January 2015.

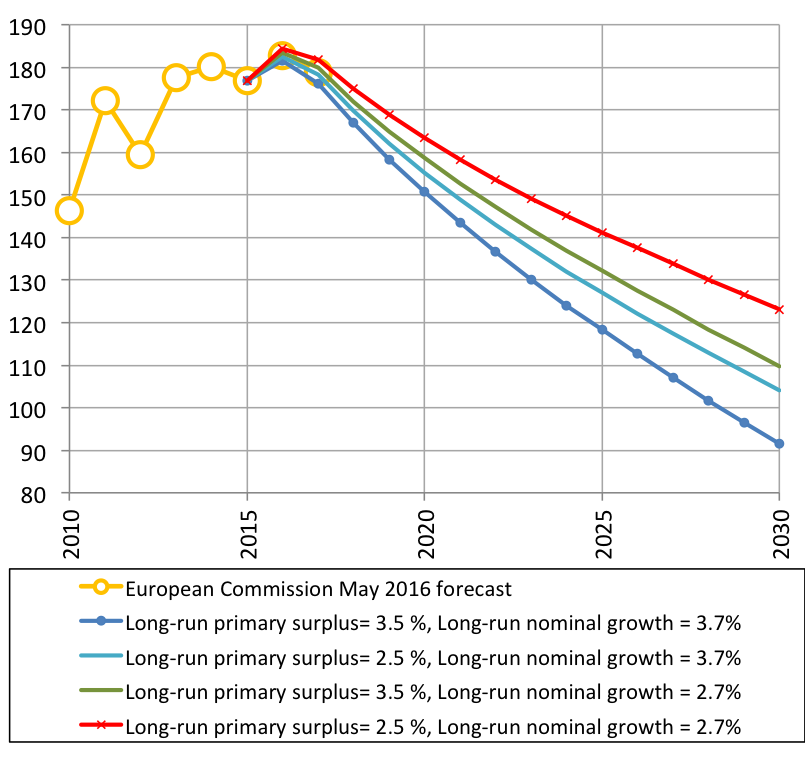

We have updated our simulations on the outlook of Greek public debt if official funding continues (see our detailed methodological description here and our calculations from January 2015 here). The results are indicated in the figure below.

Greek public debt projections (% GDP) up to 2030

Note: In our baseline scenario (blue line with symbols), the primary surplus gradually increases to 3.5% of GDP in 2018 and stays at this level thereafter, as in the 3rd financial assistance programme. For nominal GDP growth, it assumes the IMF growth forecasts by 2020, after which growth is reduced to 3.7% per year (the long-term nominal growth forecast for Spain by Consensus Economics; unfortunately Consensus forecasts are not available for Greece). We consider alternative scenarios when either the primary surplus is reduced by 1% of GDP in each year, or GDP growth 1% point slower growth in each year, or both.

Even under the assumption of a 2.5% of GDP primary surplus and a 2.7% per year nominal GDP growth, the public debt ratio is set to decline, although it looks to remain very high in the next fifteen years(**). While these calculations are sensitive to the underlying assumptions and it is difficult to envision at what level of public debt the Greek government would be able to market borrowing at an affordable cost, it is quite unlikely to happen before 2030.

Eurogroup discussion will therefore face difficult choices. Will it insist on the 3.5% of GDP primary balance target by 2018? Or allow delayed fiscal adjustment, or even a lower target? Will it agree to fund the new borrowing requirements of Greece by at least 2030 and reduce the new borrowing requirement by some lighter form of easing the debt burden, or implement a sizeable debt reduction to facilitate the return to market borrowing? Our advice is to offer hope for Greece in the form of delayed fiscal adjustment toward a target of 2.5% of GDP primary balance and adopt various measures to ease the debt burden, for the benefit of both Greece and its official lenders.

Endnotes:

(*) According to our calculations, the current ESM funding rate for Greece is about 0.7% per year, while the EFSF loans cost about 1.2% (the average funding costs of these institutions, considering outstanding bonds and new bonds and bills to be issued in 2016). Since higher-yielding bonds issued in earlier years will gradually mature and will be replaced by lower-yielding bonds, even these low average funding costs are expected to fall further till about 2020 according to market-based expectations, after which a slow increase is expected to about 1.5% in 2030. The 3-month Euribor (to which the interest rate of the €53bn bilateral loans is linked) is expected to remain negative until 2019 and only a small increase is expected thereafter. We see no chance that Greece would be able to borrow at interest rates close to the ESM/EFSF/bilateral loan funding costs, and borrowing at a much higher rate from the market would derail public debt developments.

(**) The Greek public debt trajectory has improved since our 2015 calculations, primarily due to the significant reduction in current and expected interest rates on bilateral euro-area country loans, EFSF loans and ESM loans.