A new report from eVestment looks at the relationship between the size and age of hedge funds on the one hand, and their performance on the other. Personally, though, I found the tables relating standard deviation to those factors more intriguing, but I’ll get to that.

Over the last ten years, small funds have outperformed the large, precisely because they do something that isn’t scalable.

The report observes two trends as to the size/performance link, and both of them sound like bad news to starry-eyed investors: on the one hand, the tendency of small funds to outperform is declining. On the other hand, the proportion of small funds within the industry is likewise declining. So for both reasons, hopes of finding that hedge fund shop consisting just of one or two geniuses and their clerical help, with an AUM consisting just of cash from their close friends – and now you – and of riding this discovery to the skies: those hopes are dimming.

Consolations

If it is any consolation, eVestment also describes the dimming of such hopes as part of the “maturation of the hedge fund industry.”

Also if it is any consolation: the standard deviation of small funds still looks dependably wider than that for larger funds. This might keep hope alive.

Age, eVestment continues, is probably a better guide to performance than size. “Young funds posted the highest cumulative returns since 2003” the report says, and “during the past 5 years have also outperformed mid-age and tenured funds.”

The definitions employed in reaching these conclusions are as follows:

- A young fund has been around for a period of more than 10 months (infant funds, of fewer than ten months, apparently don’t have worthwhile track records yet, it is too speculative to annualize those returns), but have been around for no more than 2 years.

- A mid-age fund, 2 to 5 years.

- A tenured fund, more than five years.

- Small funds have assets under management of less than $250 million.

- Medium funds have AUM in a range from $250 to $999 million.

- Large funds, unsurprisingly, have AUM above the medium range.

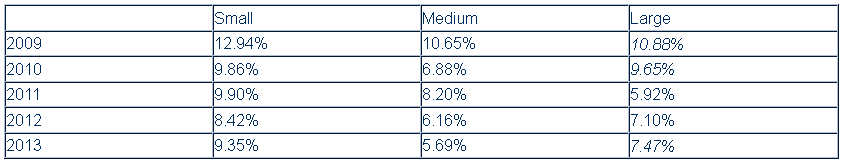

The report provides a cross sectional analysis that breaks down the standard deviation of young funds in particular this way (I’m shortening eVestment’s actual10-year table here in order to focus here on the post-crisis years).

YOUNG FUND STANDARD DEVIATION

The report cautions that the italicized numbers (for the years 2009, 2010, and 2013 in the large column) represent groups with fewer than 8 funds in the database, so those numbers might be taken with some caution.

Nonetheless, for the years covered by that truncated table the smaller young funds have always had a greater standard deviation than the other two size classes within that age group. Nothing much can be said about the relationship of large to medium size young funds here. For the two years when the large-young database is adequate, large has the greater variance in 2012 but the lesser in 2011. So what?

One conclusion you might draw is that the hope of finding those really smart managers who can deliver you a lot of alpha while they’re still small and hungry is still alive. After all, you can’t be risk averse for that purpose. You want a large variation for that purpose: you’re trying to get yourself on the winning tail of the bell curve.

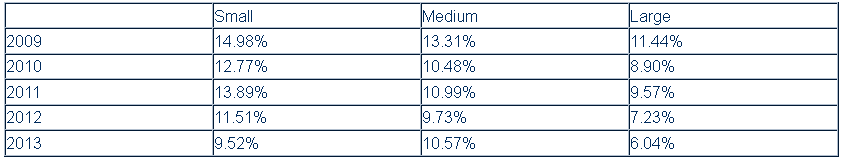

Now let’s look at the old guys, gently called “tenured” funds, and their standard deviation when broken down by size over the same period.

TENURED FUND STANDARD DEVIATION

There are no italicized numbers in this table, no indication that any of the sets are too small to be reliable.

The over-all pattern is the same, for every year other than 2013. The smaller funds are the one where you’ll find the outliers.

Which stock should you buy in your very next trade?

With valuations skyrocketing in 2024, many investors are uneasy putting more money into stocks. Unsure where to invest next? Get access to our proven portfolios and discover high-potential opportunities.

In 2024 alone, ProPicks AI identified 2 stocks that surged over 150%, 4 additional stocks that leaped over 30%, and 3 more that climbed over 25%. That's an impressive track record.

With portfolios tailored for Dow stocks, S&P stocks, Tech stocks, and Mid Cap stocks, you can explore various wealth-building strategies.